Building and history

The Correr Museum

The collection has been housed since 1922 in St Mark’s Square, in the spaces of the Napoleonic Wing and part of the Procuratie Nuove.

The design and initial building work on the Napoleonic Wing dates from the years when Venice was part of the Kingdom of Italy (1806-1814) of which Napoleon was sovereign and his stepson, Eugene de Beauharnais, was Viceroy. The site had previously been occupied by the San Geminiano Church – an ancient foundation that had been rebuilt in the mid-16th century by Jacopo Sansovino – and ran between the Procuratie Vecchie and Nuove, the two long arcades of buildings which extend the length of St. Mark’s Square and had housed the offices and residences of some of the most important political authorities of the Venetian Republic.

Originally designed as a residence for the new sovereign, the Napoleonic Wing would only be finished in the 19th century, when Venice was under Austrian rule, serving as the official residence of the Hapsburg Court on their frequent visits to the city, and would after become the Venetian residence of the King of Italy.

The building has maintained many of the distinctive features of the Napoleonic and Hapsburg periods; neo-classical influence in architecture, decor, frescoes and furnishings make it an important record of the culture and style of a period. However, the most important aspect of the Napoleonic Wing, which seems to set itself in deliberate contraposition to the old Doge’s Palace, is that this residence of kings and emperors was the expression of a desire to open up a new chapter in the history of Venice.

From the Correr Collection to the Musei Civici di Venezia

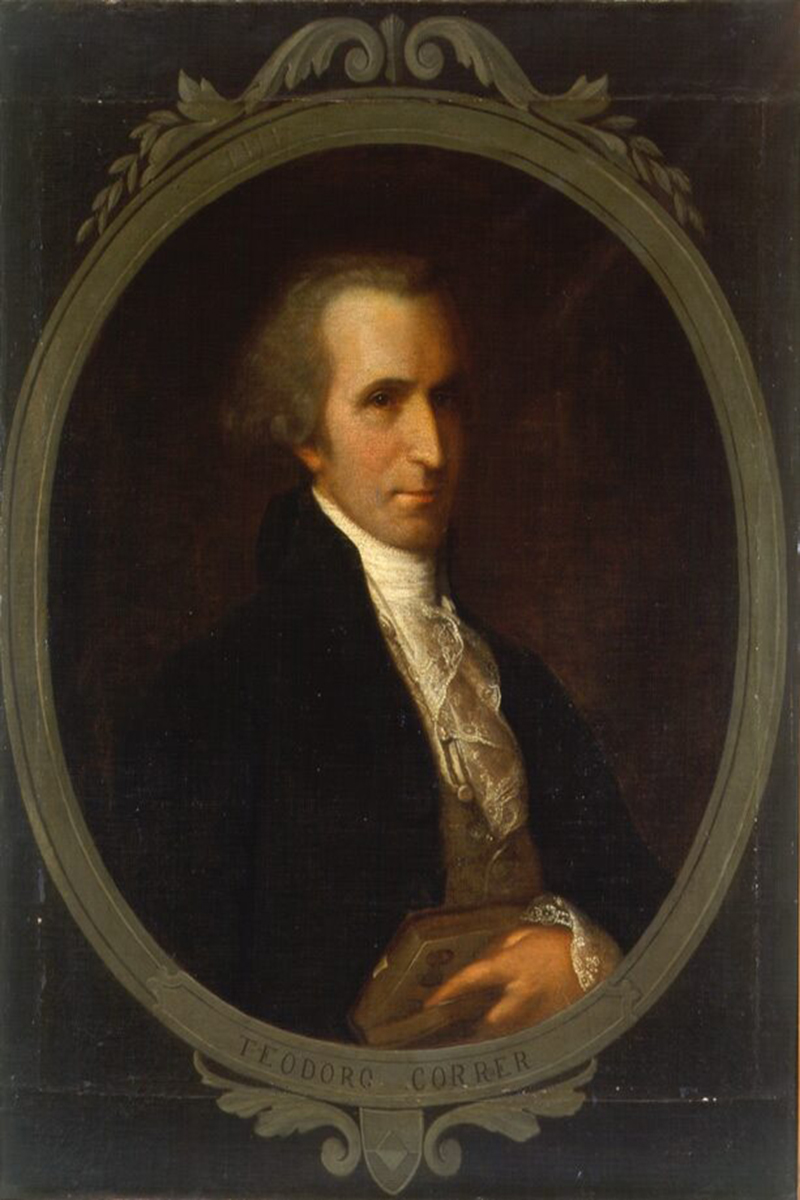

The Museo Correr takes its name from Teodoro Correr (1750-1830), a passionate art collector who was a member of an old family of the Venetian aristocracy. When he died in 1830, he donated to the city not only his works of art, but also the palazzo at San Zan Degolà in which they were housed, plus funds to maintain and further extend a collection which was to bear his name and ultimately became the core around which the Musei Civici di Venezia developed.

Correr’s will was explicit about when and under what conditions his house was to be open to the public and to scholars, how many people were to work in maintaining the collection, and even what funds were to be used for this purpose. These precise instructions indicate that what he had in mind was not only a place of scholarly research, but also a veritable museum, a place in which to collect, conserve and exhibit works of various kinds.

However, initially the collection was not on display to the public as an organic whole; and though it was opened as early as 1836, it was only with its third curator, Vincenzo Lazari, that one can say it became a proper museum.

Thereafter, the collection continued to grow through donations, bequests, and acquisitions. From this core collection, the modern-day Musei Civici di Venezia would gradually emerge; and a series of different collections would eventually become a vast network of museums spread throughout the city.

The museum was first moved in 1887 from the Palazzo Correr at San Zan Degolà to the nearby Fondaco dei Turchi, with the entire layout of the exhibits being redesigned.

In 1922, the Museo Correr was moved once again, to its present-day home in St. Mark’s Square, occupying the Napoleonic Wing and part of the Procuratie Nuove.

Teodoro Correr

Successor of an old aristocratic family, Teodoro Correr was born in Venice in 1750. Over the course of his life, he will pursue his only true interest: collecting, a passion to which he was faithfully dedicated right up to his death in 1830.

As a passionate collector, Correr was fortunate because in the last years of the Republic and the early years of the subsequent foreign rule over the city, an enormous quantity of antique objects, artworks, libraries, and whole collections were being sold off. Hence, there were remarkable opportunities for anyone trying to build up his own collection. Correr managed to put together an extraordinary amount of material.

Driven by passion, and therefore far from following the rationally-meditated plan one would expect behind a modern museum collection, Teodoro Correr nevertheless considered the objects filling the rooms of his family palazzo at San Zan Degolà as forming a museum. Thus, he made it available to scholars and donated the collection to the city with the condition that it be organised and financed as a museum open to the public.