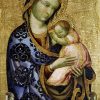

25. Paolo Veneziano and 14th century Veneto painters. Early Venetian painting is closely bound up with the traditions of Byzantium – and of the Paleologue empire in particular. Gradually, during the course of the 14th century, it would become more open to the modern and Gothic influences coming from mainland Italy. Features characteristic of Central Italian, rather than Veneto-Byzantine, painting can already be seen in the Genealogy of Christ, with the Life of Christ and the Virgin , a work of complex symbolic content which, above all in the stories depicted in the right-hand panel, reveal some influence of Giotto. A more direct link with the Byzantine tradition can be seen in the Madonna and Child, Pietà and Saints, and the Madonna and Child – works which nevertheless have a distinctly Veneto style and can be attributed to a Greco-Veneto artist of the fourteenth century. The Madonna and Child with Angels is, for its part, to be attributed to an early 15th century Cretan-Veneto artist, close to the school of Andrea Rizzo of Candia; the attempt to render the throne in perspective, and the modelling of the figures of the Madonna and Child, are clearly Western-influenced and suggest a link with the Veneto. A turning-point in painting within the lagoon would come with Paolo Veneziano, the most important of early 14th century Venetian painters and one of the most significant figures in the Gothic art of the Po valley area.

He would develop his own very personal artistic language, with a subtle balance between Byzantine and Gothic influences, even if in the latter part of his career his work might be described as neo-Byzantine. It is to that later period that the two panels St. Augustine, St. Peter, and St. John the Baptist are to be attributed. These are side panels of a now-dismembered polyptych from the parish church of Grisolera, near San Donà di Piave (the central panel was lost). The elongated figures remain faithful to Byzantine models, but the vivid colour, the richly-adorned vestments, and the artist’s care in portraying individual figures with shrewd expressions and elegant movements, all indicate the influence of Gothic art. These various influences within the artist’s work can also be seen in the fragment of St. John the Baptist, part of a much larger composition that probably came from the Venetian cathedral of San Pietro di Castello; here, the clearly Byzantine face goes together with a vivacity of colour and elegance of pose that are symptomatic of Gothic art. The painter of the St. Peter was clearly influenced by Paolo Veneziano, as one can see from the expressive modelling of the figure, whilst the St. John the Baptist painted within an aedicule reveals the influence of Lorenzo Veneziano, together with that of contemporary Tuscan art.

26. Lorenzo Veneziano. The most significant artist in Venice during the second half of the 14th century was Lorenzo Veneziano, who probably trained within the studio of Paolo Veneziano. Whilst clearly receptive to the influence of his master, this artist would develop a more decidedly Gothic artistic language. But while responding to the painting of mainland Italy – especially that of the Po Valley area, where some echoes of Northern Europe might be felt – Lorenzo Veneziano also maintained the Byzantine tradition in works characterised by great elegance of line and striking limpidity of palette. In the panel with Saints Julian (?), Mark, Bartholomew; three stories of St. Nicholas; the Saints Gabriel, Ursula and Lucy – the extant central part of a now-lost polyptych – he reveals his independent artistic personality both in his use of colour and in his composition of the scenes (above all, in those regarding the life of St. Nicholas, which are characterised by great immediacy and vivacity). The frame, modelled on a three-light Gothic window, is also original for this period. The panel of Jesus giving the Keys to St. Peter is dated 1369 by the Venetian calendar of the day (that is, 1370), and was part of a polyptych, the predella panels of which (Life of St. Paul and St. Peter) are now in the Staatliche Museen in Berlin. Here, the artist adopts a monumental composition, accentuating the space of the picture through the construction of the marble throne surrounded by angels and saints. The richness of Jesus’ vestments and mantle, the latter creating a play of chiaroscuro as it falls in soft folds, belong to a clearly Gothic artistic language, in which one can see influences from the Po valley and Emilian regions. Recent cleaning has restored the splendid enamel-like colour which is one of the unmistakable trademarks of the artist’s work. The Crucifixion with Saints is the work of a Veneto-Byzantine artist and can be dated to the first decades of the 14th century; the respect for Byzantine iconographical models is here relaxed a little in the everyday humanity of the faces – a clearly Venetian trait. The four panels with Saints John the Baptist, Paul, Peter, and Andrew were formerly attributed to the circle of Lorenzo Veneziano, but now are attributed to his follower Jacobello di Bonomo, who is known to have been active in the period 1375-1385.

27. Flamboyant Gothic. Gothic Art in Venice was to flourish long and successfully, particularly in the fields of domestic, public and religious architecture, playing a key role in establishing the layout and appearance of the city. Evidence of this is to be seen in two fragments of fresco decoration discovered during work on a house at San Giuliano, near St. Mark’s, in the early 1900s. Transferred to wood panels, these fresco fragments were then acquired by the Museum as rare works that offer priceless evidence regarding the development of taste and the layout of domestic interiors in 14th century Venice. They depict four allegorical figures of the Virtues: on one, Charity, Constancy, Hope; on the other, Temperance. Each with their identifying emblems and symbols, these sit within Flamboyant Gothic seats decorated with aedicules and small statues. Though with clear Venetian features – especially in the palette used – the works reveal the presence of mainland influences that can be traced to the Padua area. Though dating from an earlier era (late 13th and early 14th century), for conservation reasons the Casket of the Blessed Giuliana di Collalto is also on display in this room. Originally from the church of Santi Biagio e Cataldo on the Giudecca, this has a lid whose inner side is decorated with images of the saint, who died in 1262, and the two saints after whom the monastery was named. It is probably the work of a local artist, revealing a very Western attention to expression that clearly has little to do with Byzantine influences. The rather crude decorations on the front of the casket date from substantially later. The room also contains a number of works of sculpture from this period: a fragment of a doorway from Palazzo Bernardo in the San Polo district, a fine Gothic marble transenna and three pinnacles in Istrian stone (probably part of an altar, these reveal a French influence). Jacobello dalle Masegne’s small marble statue of Doge Antonio Venier is a little masterpiece by the artist who was also responsible for the Iconostasis in St. Mark’s Basilica. No generic representation of a public figure, the statue is a veritable portrait, revealing the inner strength and intensity of meditation of the sitter.

28. Gothic painting. Whilst still maintaining the severity of neo-Byzantine work, the numerous panel paintings by the artists who followed Lorenzo Veneziano reveal the influence of mainland Italy in various ways: their powerfully compact modelling, their monumentality, their affectionate interest in the natural world. Whilst the two figures of Christ on either side of the lobate Processional Cross are most clearly indebted to Byzantine models and the mosaics of St. Mark’s, the artistic language of Lorenzo Veneziano certainly makes itself felt in the work of the “Master of the Madonna Giovannelli”, whose Coronation of the Virgin nevertheless reveals more incisive brushstrokes in its creation of substantially corporeal figures. Neo-Byzantine features and Gothic influences appear together in the work of Federico Tedesco, represented here by the complex composition of the Allegory of Redemption and the altarpieces and compartments with St. John the Baptist, St. Paul, The Annunciation and (in the cyma), the Death of the Virgin.

His expressive immediacy and overall gentleness of tone mean that the anonymous artist known as the “Master of the Correr Wall Panel” – after the work conserved in the museum – occupies a very special place in Venetian painting at the end of the 14th century. The Madonna with St. Paul and St. John is to be attributed to a Rimini artist, who is now rightly identified with the so-called Maestro dell’Arengo. Stefano Veneziano, Jacobello di Bonomo and Gothic Painters One particularly noteworthy figure amongst the artists working in Venice in the last decades of the 14th century was Stefano di Sant’Agnese, whose name indicates he was a plebanus – that is, parishioner – of the Venetian church dedicated to the saint. He stands out amongst the various artists of the day who offered a more fluid form of the learned style developed by Paolo and Lorenzo Veneziano. The delicacy of form and elegance of line in his work reveal clear awareness of Gothic art, with some, timid, openness to the style of International Gothic. The rich decoration and architectural definition of the throne in his Madonna and Child – dated 1369 in the Venetian calendar (that is, 1370) – are certainly influenced by the work of Paolo Veneziano, whilst the pyramidal composition of the figures and the naturalistic rendition of the gentle facial features seem to indicate a close link with the painting of mainland Italy. Part of a polyptych originally in the Scuola dei Forneri [Bakers’ Guild] near the church of Madonna dell’Orto, his St. Christopher is the artist’s last known work (1385) and reveals great vigour in the modelling of the figure (three other panels from that polyptych are now in the church of San Zaccaria). An artist more closely bound to tradition was Jacobello di Bonomo, who is credited with two panels here: Saints Peter and Andrew and Saints John the Baptist and Paul, which are from a much larger polyptych.

The elongated limbs and severity of the facial features (St. Peter and St. Paul almost appear to be frowning) might be taken as a return to Byzantine models; however, for all their monumentality, the figures are realistically modelled, and there are very refined decorative elements in the composition.

29. The early 15th century. In the early 15th century Venice, only uninteresting and out-of-touch artists who continued to take the Byzantine tradition as their model. The city’s expansion onto the mainland was by this point leading to contacts with other Italian and European capitals and an important interchange of cultural influences. What is more, work on the Doge’s Palaces was attracting such renowned artists as Gentile da Fabriano, Michelino da Besozzo and Pisanello, who made a key contribution in introducing International Gothic into the city. This was the cultural climate within which the double-sided panel painting of Angel Musicians (recto) and San Cosma (verso) was painted; it was probably the door of a triptych and is to be attributed to a follower of Michelino da Besozzo; whilst the painting of The Nativity within a lozenge-motif frieze is the work of an unknown artist, but does seem to reveal the influence of Jacobello da Fiore and Michele Giambono. Characteristic features of both these works are a taste for sumptuous and refined decoration, which sometimes results in the composition of complex abstract patterns. The influences to be seen in the Venetian Francesco de Franceschi’s small panels of the Martyrdom and Death of St. Mamante more clearly herald the coming of the Renaissance. From a dismembered polyptych whose various parts can now be seen in different collections, these works seem to echo the influence of both Giambono and Alvise Vivarini. International Gothic One of the most important exponents of the International Gothic school of painting in Venice was Michele Giambono, who was not only a painter but also a mosaicist (he worked on the cartoons for the Madonna dei Mascoli chapel in St. Mark’s Basilica). Particularly influenced by the example of Gentile da Fabriano and Pisanello, he reveals himself in his Madonna and Child to be an artist of elegant decorative compositions, whose refinement of palette has been further underscored by recent cleaning of this particular work. Another important artist of the International Gothic school was Jacobello del Fiore, who in 1415 painted the Lion of St. Mark for the premises of the Magistrato all Bestemmia [Blasphemy court] in Palazzo Camerlenghi at Rialto, and in 1421 the Justice Triptych for the Magistrato del Proprio [Property, Dowry and Inheritance Court] at the Doge’s Palace (the work now hangs in the Accademia Gallery). The Madonna and Child here is recognised as one of the works most representative of the artist’s style, its most striking features being the handling of the light-blue mantle with arabesques of blue flowers and the use of rose-headed stamps to achieve a raised decorative effect along the hem of the gown and around the haloes. However, it is the gentle, aristocratic reserve in the way the Virgin embraces the Child that reveals most clearly the influence of courtly Gothic – and of the work of Gentile da Fabriano in particular. Two works that are useful in a comparison between the International Gothic of Venice and that of Central Italian are the Saint Ermagora and Saint Fortunatus. The side panels of a triptych (the central Madonna and Child is now in a private collection in Paris), these are the work of Matteo Giovanetti of Viterbo, an assistant to Simone Martini who would actually take over from his master in the work on the decoration of the Papal Palace in Avignon. The “Master of the Jarves’ Coffers”, a Tuscan artist of the first half of the fifteenth century, is credited with the two coffer panels (cl. I, 516) with the Story of Alatiel, inspired by Boccaccio’s Decameron.

30. Cosmè Tura. One of the most influential artistic figures in Ferrara during the middle and late periods of the 15th century was Cosmè Tura, whose very personal style combined the main artistic influences at work in the city: the monumentality of Piero della Francesca, the archaeological learning that was such a part of the Padua School (Tura may have stayed in that city in the mid 1450s) and the North European taste for colour to be seen in the work of Rogier van der Weyden (some of whose paintings were owned by Lionello d’Este, Lord of Ferrara). Critics universally recognise that the Correr Pietà is one of the artist’s most significant works, both in terms of style and of composition, fully exemplifying all the painter’s monumentality in spite of the reduced size of the picture (which would suggest it was intended as a private devotional image). The iconography is to be linked with German Vesperbilder, sculptural groups of the dead Christ in the lap of his mother which were associated with the Vespers of Good Friday (and thus with the Liturgy of the Passion). X-ray examination carried out during restoration work a few years ago revealed the existence of an exceptionally high-quality and detailed preparatory sketch for this intense poetic image of enormous pathos. The Portrait of a Man is to be attributed to a painter very close to Tura; once again, the incisive and accurate details reveal the influence of the Flemish School.

31. The Ferrara School. The artists of the 15th century Ferrara School had an important influence on the development of Venetian artists of the time, and the Teodoro Correr collection contains significant examples of their work. Antonio Leonelli da Crevalcore was a Bolognese-born member of the Ferrara School, and it was probably he who painted the Portrait of a Young Man, with the figure shown in dazzling colours within a frame of polychrome marble and set against a green curtain which is partially pulled back to reveal a view of a coastal city; the presence of the prayer book with the ring and pearl have led some to argue this was one part of a marriage diptych. Whatever the truth, this is a work in which incisive portraiture goes together with miniaturist precision in the rendition of the landscape. Similar incisiveness can be seen in the Portrait of a Woman. The work of a mid-century Ferrara School artist – perhaps Angelo Maccagnino (Angelo di Pietro da Siena) – this clearly reveals the influence of Pisanello’s portraits. Another painting that can be attributed to the Ferrara School is the Death of St. Jerome; a work of ethereal atmosphere, this originally went together with another two small panels paintings (now in the Brera) from the Venetian Scuola della Carità. Padua was another artistic centre that was a fundamental point of reference for Venetian painters, who were influenced by the innovations in the work of Squarcione and his circle, and – above all – by the example of Andrea Mantegna.

The Flagellation is by a follower of Mantegna, Pietro da Vicenza, whilst the Madonna and Child – restored to its original splendour of colour by recent restoration – is the work of Giorgio Chiulinovich, known as Lo Schiavone [The Dalmatian], who trained under Squarcione. The influence of that artist – together with that of the Tuscan School as represented by Piero della Francesca – can be seen in the work of the Verona-born Francesco Benaglio, whose Madonna and Child seen against a wide hilly landscape combines the example of della Francesca with a much more incisive, graphic use of line.

Bartolomeo Vivarini and Leonardo Boldrini With Bartolomeo Vivarini – who produced a number of works with his brother, Antonio – one comes to what may be described as Venetian painting proper. Maintaining a very active studio in the city for a number of years, Bartolomeo Vivarini was one of the leading figures in that shift within Venetian painting from Late Gothic to Early Renaissance. Receptive to innovations that Mantegna and the followers of Squarcione had introduced in Padua, Vivarini would – whilst preserving the old notion of a gold background – give a very modern rendition of such a traditional theme as the Madonna and Child. There are two fine examples of such works in the Correr; though the former has an extensively repainted background, in both of them the faces are remarkably gentle, with a hint of restrained sorrow. The Murano-born Leonardo Boldrini would train under Vivarini, but also show himself open to the influence of Lazzaro Bastiani and Giovanni Bellini. Bartolomeo Vivarini, however, seems to be the main influence in his Madonna with St. Jerome and St. Augustine, in which the figure of the Virgin actually seems to be taken whole from Bartolomeo’s Ca’ Morosini polyptych, now in the Accademia Gallery. The two later panel paintings – The Nativity and The Presentation in the Temple – have a sharpness of perspective that reveals the clear influence of Bastiani.

32. The Four Doors Room. This is one of the very few rooms in the Procuratie Nuove that has retained intact its original structure, dating from the late 16th and early 17th century. The only addition to Scamozzi’s original design are the two side doors (now bricked in), which probably date from the 18th century – as do the two large Murano chandeliers. The room is furnished with sixteenth- and seventeenth-century furniture and chairs and some examples of fifteenth-century wooden sculpture.

33. 15th century Flemish painters. The museum possesses a large collection of Flemish paintings, most of them acquired within the city during the nineteenth century by Teodoro Correr – further proof of the close relations that had existed between Venice and Northern Europe over the course of the centuries.

One work that stands out is The Adoration of the Magi by Pieter Brueghel the Younger. This is one of a series of works in which the younger artist took his inspiration from a painting of the same subject by his father, Pieter Brueghel the Older (now in a private collection in Winterthur), introducing a number of variations into his own versions of the work. X-ray studies during recent restoration work revealed the presence of a very detailed preparatory drawing for this minutely-analytical work, in which the miniaturist rendition of detail is so complete that some can only be seen with the help of a magnifying-glass. This same, typically Flemish, attention to minute detail can be seen in a number of other works, whose artists are yet to identified with certainty. Particularly significant paintings include the Madonna and Child – which is tentatively attributed to Dieric Bouts – and the two doors with The Annunciation (recto) and St. Zaccaria (?) and St. Joseph (verso), recently attributed to a Flemish artist active around 1490.

34. Antonello da Messina. Antonello da Messina arrived in Venice in the winter of 1474-75, staying there until the autumn of 1476. Venetian documents record his presence in the city and his relations with the nobleman Pietro Buon, who commissioned from him the large altarpiece for San Cassiano (parts of which are now in the Vienna Kunsthistorishes Museum). The artist was to be a decisive influence on the emergence of the great Renaissance School of Venetian painting. From his work, which combined both Tuscan and Flemish influences, Venetian artists would seem to have learnt the technique of oil painting (though there are still some doubts on this matter) and also the correct application of perspective; and, for his part, from his stay in the city, Antonello acquired a new interest in colour, which would enrich and modernise his own artistic language. The Pietà is the only work left in Venice to bear witness to the artist’s presence in the city. As source documents indicate, it was originally hung in the Chamber of the Council of Ten in the Doge’s Palace, and although it has suffered damage and mutilation at the hands of past restorers, it still maintains the charm and power of Antonello’s art. It is also interesting to note that though the subject of the Pietà was frequently explored by Mantegna and Bellini, this is the only known version of the theme painted by Antonello da Messina. The landscape behind the figures is particularly interesting, incorporating as it does the Messina church of San Francesco. Two other masterpieces in this room bear witness to the artist’s close links with contemporary Flemish painting: Hugo van der Goes’ Crucifixion, a work that combines sobriety with intense dramatic power, and Dieric Bouts’ Madonna and Child, in which the small crown of pearls symbolises the virgin birth and the coral the future sacrifice of Christ (further indicated by what looks like a small shroud).

35. Flemish and German painters. The paintings in this room are by Flemish and German artists active between the end of the fifteenth and the middle of the 16th century. The panel with The Revels of the Prodigal Son has recently been attributed to the circle of the Flemish artist Paul Coeck. The scene is set outside an tavern, as one can see from the inn-sign fixed to a tree – on which wagers have been marked up – and the glasses of wine and the fruit on the table. An Antwerp-born follower of Bosch is credited with The Temptations of St. Anthony, which is, in effect, a pastiche of Hieronymus Bosch’s own paintings of the subject. The various allegorical components in the work include the huge human head with the gaping mouth, the group of nude figures, and the gold- and silverware being offered by the devil; respectively, these symbolise the gaping gateway to Hell, the temptations of the flesh, and those of vanity and riches. The Adoration of the Magi, around 1529, is attributed to an unknown German artist; recent cleaning has restored the original colours of the work. And the Lucas Cranach signature on painting of The Resurrected Christ is apocryphal; the work is probably to be attributed to one of his followers. The refined portraiture of the German artist Barthel Bruyn the Elder is very clear in hisPortrait of a Gentlewoman; the elegance of the gown and the opulence of the jewels and the girdle – clear indications of the sitter’s social status – are deliberately counterbalanced by the skull, which indicates the ephemeral nature of worldly possessions. The two panels with St. Barbara and St. Catherine (collection of the Accademia Gallery) are part of a polyptych by Jos Amman von Ravensburg (Giusto d’Alemagna), the various parts of which are now to be seen in Venice, Modena and Lüttich. The artist – a native of Ravensburg, which lies between Lake Constance and the Upper Rhine – is also known to have worked in Genoa, where his presence is documented in 1451. The Nativity and the Presentation in the Temple are again parts of a dismembered polyptych – this time by Rueland Frueauf, whilst the Virgin and Child with Choir of Angels is by the German artist Hans Fries.

It is the central part of an altarpiece, the side panels of which are also part of the museum’s collection.

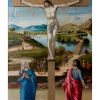

36. The Bellini Family. The Bellini family provided some of the most important Venetian painters of the 15th century: the father, Jacopo Bellini, and his two sons, Gentile and Giovanni. After training under Gentile da Fabriano, who was in Venice from 1408 to 1414 to paint the history frescoes in the Chamber of the Great Council within the Doge’s Palace – Jacopo Bellini would then follow his master to Brescia and Florence; the latter city played an important role in exposing him to the climate of the Early Renaissance. The Crucifixion, of around 1450, is considered to be part of a predella from a polyptych (perhaps in the monastery of San Zaccaria) which also included the Adoration of the Magi and Christ’s Descent into Hell (now in the Ferrara Pinacoteca Nazionale and the Padua Museo Civico respectively). The composition here is traditional: in the centre is Christ on the Cross, to his right, Mary supported by the holy women (with a group of soldiers in the background), and to the left, a sorrowful St. John the Evangelist and the kneeling figure of Longinus recognising that this surely was the Son of God.

The low horizon isolates the figure of Christ against the sky, lifting him above the actions and sorrow of those present. Jacopo’s elder son, Gentile, was the painter of the Portrait of Doge Giovanni Mocenigo (cl. I, 16), which though unfinished is one of the most important extant demonstrations of his skill as a portrait artist (a skill so renowned that, in 1479, Gentile was included as part of a Venetian diplomatic mission to Constantinople, where he painted the Portrait of Sultan Mehmet II which now hangs in the National Gallery, London).

Though an easily recognisable likeness, this portrait – taken in profile – does not strive to render the physiological individuality of the sitter himself; it is the Doge – the very symbol of the Venetian Republic – who is being depicted. Jacopo’s younger son, Giovanni, would dominate the world of Venetian painting in the second half of the fifteenth century.

Having trained under his father, he soon established himself as an independent artist, at the head of a very busy studio which would continue to be active until around 1515. Receptive to the lessons to be learnt from his brother-in-law, Andrea Mantegna, and influenced by the work of Antonello da Messina, Giovanni would develop a very refined – and in some ways, erudite – artistic language. The Crucifixion (cl. I, 28) of 1453-55 belongs to the early stages of the artist’s career. There is a sharp break between the minutely-detailed background landscape and the foreground occupied by the drama of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross, here read as an historical event to be set within daily life.

The influence of Mantegna is clear in the modelling of the figures, which achieve a certain monumentality in spite of the reduced size of the panel (the scale of the work suggests that it was painted as a private devotional image).

Around the same time, the artist painted the Pietà (cl. I, 39), the atmospheric composition of which echoes that to be seen in a bronze bas-relief of the same subject that Donatello produced for the High Altar of the Basilica del Santo in Padua around 1447–48. The Transfiguration of Christ can also be dated around the same time. Damaged in the upper section, this depiction of Christ on Mount Tabor was probably the altarpiece in one of two Venetian churches: San Salvatore or San Giobbe.

The Madonna and Child – also known as the Frizioni Madonna, after the owner who donated the work to the museum in 1919 – dates from around 1470–75. Though transfer from panel to canvas has damaged the painting, and the sky has been repainted, the work is fine example of Giovanni Bellini’s inventive creativity: no other work of the time depicted the Virgin in this way, with a purple gown, a pink mantle and a veil – only half covering her head – held in place by a brooch. The Christ Child she is holding seems lost in thought as he rests his feet on a parapet, which symbolises not only the sarcophagus in which He will be buried but also the altar on which His death and resurrection will be celebrated in the Mass. The two small paintings with Portrait of a Young Saint crowned with Laurel and Doge Pietro Orseolo and Dogaressa Felicita Malipiero are to be attributed to Giovanni’s studio; the latter is the sole extant fragment of the predella of a polyptych originally painted for the church of San Giovanni Battista on the Giudecca. All of these works by the Bellini family have undergone recent restoration; and x-ray examination carried out as part of that process revealed the presence of detailed preliminary sketches underneath each.

37. Alvise Vivarini and his time. Various contemporaries of Giovanni Bellini were well-aware of the lessons to be learnt from his work and yet developed their own art independently. The easel-work St. Anthony of Padua – in its original frame – is by Alvise Vivarini, son of Antonio and grandson of Bartolomeo, hence the last member of a family dynasty of painters which played such an important role in introducing the artistic languages of Mantegna and the Padua School into Venice. A work of refined and elegant line and very delicate palette, this painting is the artist’s copy of part of another of his works – the polyptych which now hangs in the Accademia Gallery. In his Sacra Conversazione – signed and dated 1498 – Giovanni di Martino of Udine appears to be an artist who was very close to Alvise Vivarini; whilst Benedetto Diana and Pietro Duia – represented here by a Pietà, Madonna and Child, two Saints and Donors and Madonna and Child – would seem to have been much closer to the Bellini circle. The influence of Alvise Vivarini can also be seen in the work of Jacopo da Valenza, who worked largely in the area of Belluno, where he was born; he is represented here by The Madonna suckling the Child – signed and dated 1488 – and Madonna worshipping the Christ Child. Though damaged, Cima da Conegliano’s Madonna and Child with St Nicholas and St. Lawrence – dating from the second decade of the 16th century – reveals the artist’s atmospheric handling of volume and his bright, enamel-like palette. The small Madonna and Child with Angels – with its intensely spiritual, meditative figures set against a gentle, rolling landscape – is by Lorenzo Lotto. Most refined in palette, the painting can be dated around 1525. Bartolomeo Montagna was a Vicenza-born artist whose main influences were Giovanni Bellini and Antonello da Messina. He is to be attributed with the Santa Giustina – whose rather rigid composition also reveals the influence of Vivarini – and the later Madonna and Child with St. Joseph, with robustly-modelled figures and bright surfaces of colour. Marco Basaiti’s Madonna and Child with Donor is universally held to be an early work. The artist would work with Alvise Vivarini for a number of years and the influence of the older painter is very clear here – above all, in the brilliant, enamel-like palette.

38. Vittore Carpaccio. The Two Venetian Gentlewomen is one of the most famous works by Vittore Carpaccio, the great Venetian painter of narrative cycles, famous for his St. Ursula Cycle (now in the Accademia Gallery), the episodes in the lives of St. George, St. Tryphon, St. Jerome and St. Augustine (still in the Scuola San Giorgio degli Schiavoni for which they were painted) and the St. Stephen Cycle (now split up between various galleries in Italy, Germany and France). In the past, Romantic art criticism had given this painting the title The Two Courtesans, but the sitters are clearly two gentlewomen, whose elegant garments and hairstyles clearly denote their wealth, their status – and their honesty. With regard to this last point, the virtue of the two ladies is underlined by various symbolic details: the pearls around the neck of the younger woman indicate rigorous respect of marriage vows (as well as social status), whilst the snow-white kerchief is a sure sign of purity. Similarly, the doves, the peahen and the dogs are, respectively, symbolic of modesty, marital concord, fidelity and vigilance (the last further guaranteed by the presence of the older woman, perhaps the mother or elder sister of her companion, whom she resembles) What is more, the vase of myrtle and the orange were plant motifs that were traditional associated with the Virgin Mary (and the coat-of-arms on the vase is clearly that of an old Venetian family, the Preli). Details of costume make it possible to date this exceptional painting around 1490-95. The work has been cut across the top, and that missing part is nowadays identified with panel-painting of A Scene of Hunting in the Lagoon (Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), in the lower section of which appears the lily which emerges from the vase with the coat-of-arms. Hence the subject-matter of the entire picture becomes clearer, with two noblewomen becoming perhaps slightly bored as they wait for their husbands to return from a hunting trip. The St. Peter Martyr is a late work by Carpaccio. The polyptych of which it was part was originally in the Venetian church of Santa Fosca, but was broken up during the suppression of religious houses ordered by Napoleon; two parts, St. Roch and St. Sebastian (the latter signed and dated 1514) are now to seen in the Bergamo Accademia Carrara and the Zagabria Academy respectively.

39. Carpaccio and the minor artists of the 16th century. Only recently has the Madonna, Child and St. John the Baptist been identified with certainty as an early work by Vittore Carpaccio; in the past it was considered a later copy of a work (now in the Frankfurt Sädelsches Kunstinstitut) whose attribution to Carpaccio has never been questioned. In spite of the extensive damage to the work, recent restoration – made possible by the contribution of Save Venice Inc. – has brought out the great quality of the painting, and x-ray examination has revealed some changes between the original sketch and the final work. Probably this is a work which, before the Napoleonic suppression of religious houses, was in the monastery of San Giacomo. The Gentleman in a Red Beret, painted between 1490 and 1495, has recently been attributed to an artist of the Bologna/Ferrara area. This high-quality work has, over the years, been attributed by critics to a number of artists – even Carpaccio himself (with reservations) – but it is the clothing which supports the claim in favour of a Bologna/Ferrara artist: the short cloak, jerkin and, above all, the beret, were no part of the contemporary Venetian wardrobe. Lazzaro Bastiani was an artist who studied under –and collaborated with – Gentile Bellini, whilst also being open to the influence of Antonello da Messina. He is represented here by the triptych of Madonna and Child with Annunciation with a rather schematic background landscape; his studio is to be credited with The Visitation. Various artists represented in this room gravitated around the Bellini circle: Vincenzo da Treviso, known as Dai Destri, whose Presentation of Jesus in the Temple is derived from a Bellini original; Marco Marziale, who himself proclaims his debt to Giovanni Bellini in his Circumcision of Christ, dated 1499; and Marco Palmezzano, whose Christ with the Cross and Saints is derived from a composition that was often used by the Bellini studio. Giovanni Mansueto was a pupil of Gentile Bellini, and his St. Martin and the Beggar reveals a certain crudity of composition; whilst Pasqualino Veneto is an artist of whom we have little information and few extant works, but he was probably a follower of Cima da Conegliano. His Madonna and Child with Mary Magdalene, signed and dated 1496, has a rather cold blue-dominated palette.

40. Artists of the Bellini circle. A native of Bergamo, Gerolamo Santacroce worked in Venice, where he had a studio. A collaborator of Giovanni Bellini’s he never forgot his master’s example throughout the course of his long career. Other important influences on this rather eclectic artist were Cima da Conegliano, Lorenzo Lotto, Carpaccio and Giorgione. The Madonna and St. Joseph is from a larger composition that must have depicted a Nativity. Here, the softness of tone and gentleness of touch reveal the influence of Giorgione. Gerolamo’s son, Francesco Santacroce, would continue in his father’s footsteps. His Vision of St. Jerome is based on a work by Parmigianino, whilst his Madonna and Child, St. John the Baptist and Two Angels is still clearly 15th century in style, with a certain coldness of palette in the landscape. The Madonna and Child with Santa Giustina and St. John the Baptist and the Madonna and Child are by Boccaccio Boccaccino, a Ferrara-born painter who worked mainly in Cremona; his artist language reveals traces of Bellini, Cima da Conegliano and the art of Lower Lombardy. The room also contains three works of 16th century sculpture: the bronze Bust of a Young Man, probably by Andrea Ricco; the marble Bust of Carlo Zen by Giovanni Dalmata; and the Tombstone of Marcantonio Sabellico, produced by the workshop of Pietro Lombardo. The display-cases contain French, Venetian and German works in ivory dating from the 16th and 17th centuries.

41.Greek painters of Madonnas in Venice. Venice had always had close links with the Eastern Mediterranean. The presence of the Venetian Republic as a political power in Cyprus, Candia and the Peloponnese clearly encouraged cultural interchange, and a large number of so-called Madonneri – Greek painters of iconic madonnas – would open up studios in the city, producing works in which the archaic traditions of Byzantine art were combined with influences from the most innovative of Venetian painting. Domenico Theotocopoli, better known as El Greco, trained as an artist in Venice. Open initially to the influence of Titian and then to that of Tintoretto, he is certainly the most famous of this group of Greek artists and is represented here by two early works: The Last Supper and St. Augustine in Prayer with the Virgin and Christ on the Cross. Giovanni Permeniate, a Greek working in Venice towards the end of the seventeenth century, painted The Virgin Enthroned between St. John the Baptist and St. Augustine (?); his only signed work, it shows how the Byzantine tradition could be wedded to influences from 16th century Venetian painting. Emanuele Zane of Candia was another Greek artist working in 17th century Venice. A priest at the church of San Giorgio dei Greci, he painted the St. Spiridion, to the sides of which are scenes from the life and miraculous works of the saint. Teodoro Pulakis was working in Venice from 1648, and was the artist of two signed paintings united in a single panel – King David Espies the “Shunammite” Woman Bathing and The Nativity – in which the brilliance of the palette is enhanced with touches of gold. The Cretan-born Michele Damaskinos worked in Venice and the Veneto in the second half of the seventeenth century; perhaps he is the artist of The Marriage Feast of Cana, a free copy of the Tintoretto work that hangs in the Sacristy of the church of Santa Maria della Salute.

42. 15th and 16th century Majolica. The important works of Renaissance Italian ceramics on display in this room are intended to provide an overview of the various schools of ceramic-ware represented in the museum collection. The large basin with Neptune on a Seahorse was produced in Pesaro, whilst the display-case to the left contains various examples of Urbino ceramics, including a fruit dish with grotesques and a central decoration showing The Three Graces. Moving rightwards, there are works by Maestro Giorgio Andreoli of Gubbio: a small tondo with armorial bearings (signed on the back) and a sweet dish decorated with a Bust of Alexander the Great. The next showcases contain works from Casteldurante and Venice, including a tile with a portrait of Doge Tommaso Mocenigo (attributed to Maestro Domenico) and the large jug decorated with Peleus and Thetis. The second showcase along the entrance wall and the one opposite it contain works by Orazio and Flaminio Fontana, ceramicists who worked in Casteldurante and Urbino; the outstanding pieces include Flaminio’s plate with The Judgement of Paris and two guastada (flasks with flattened bodies) by Orazio, decorated with the Four Cardinal Virtues.

Then come works from Faenza – including the large tile which is dated and decorated with the Rape of Helen – and ceramic-ware by Nicola da Urbino. The following cases are dedicated to Francesco Xante Avelli, who was born in Rovigo and worked in Urbino from 1530 onwards; his works here include a series of plates decorated with mythological subjects and the guastada with The Death of Psyche. The canvas above the door is The Supper of St. Dominic by Leandro Bassano and dates from the end of the 16th century.

43. The Library. The walls of this room are lined with elm-wood bookcases dating from the second half of the 18th century; designed in two classical-inspired architectural orders, they were originally located in Palazzo Manin on the Grand Canal. The antique books are of various provenance and periods. The, typically Gothic style, bronze lectern in the form of an eagle is probably of English origin and dates from the end of the 15th century. It comes from the Monastery of San Giovanni e Paolo. The Bust of Tomasso Rangone set between the windows is to be attributed to Alessandro Vittoria. The imposing 18th-century Murano glass chandelier is also noteworthy.